Water Under the Bridge? Questions and Challenges in the Central Ravine

By: Andrew Ward

When it comes to major construction projects, the Classical world remembered attempts to control and channel water as keenly as more canonical architectural monuments. Archaic and Classical figures from the tyrant Polycrates to the Persian king Xerxes were either hailed for, or railed against, for the hubris of controlling water. By the Hellenistic period and the successor kingdoms of Alexander the Great, aqueducts, channels, and other water management networks were a tool that everyone from kings to local politicians could use to gain public favor. Water management remained a major tool of later Roman largess and control in the capital and in the provinces. The impact these projects had on ancient viewers is only now coming to be fully appreciated by modern archaeologists.

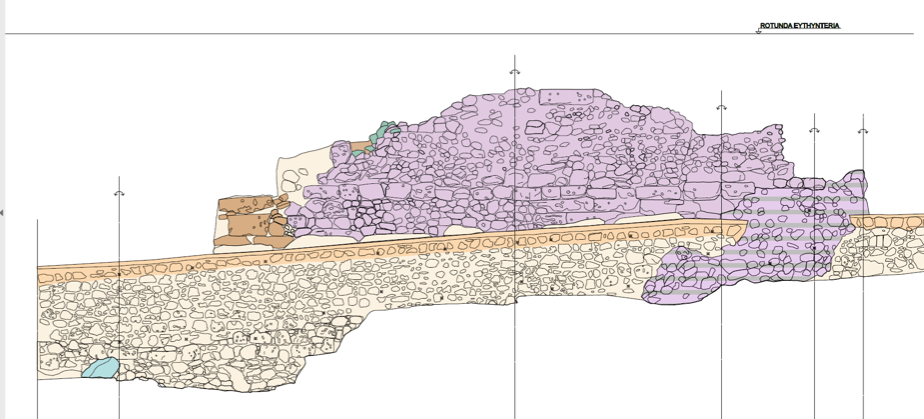

Along these lines, the “Central Ravine,” a channel that runs roughly south-north through the central valley of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods, became the subject of formalized and intensive study in 2016 and 2017. The core of this work utilized photogrammetry, a method of creating a 3d model by stitching together many digital photographs. Archeologists rendered two dimensional plans, such as the one pictured above, from the 3d model allowing archaeologists to quickly document a physical feature of the Sanctuary whose great length would require years of planning using traditional hand measurements. This work, bringing together multiple specialists, is part of the wider growth of the Digital Humanities in American archaeology.

The primary objectives of our study of the Central Ravine are to understand the course, dimensions, and magnitude of the ancient (Greek and Roman period) water channel, and how the channel was bridged and thus shaped an ancient visitor’s experience of the Sanctuary. Fortunately, along the modern ravine small sections of the ancient ravine are visible. In the image below, for example, a section of the modern retaining wall is visible on the left, while a section of the ancient wall of the ravine is visible on the right. The Greek period walls visible in this image, made by stacking roughly worked basalt boulders give way to stretches of Roman period walls composed of concrete and reused blocks, all integrated into a modern ravine lining built and rebuilt from the 1950s until today.

The most remarkable aspect of the project was coming to understand the dynamism of the Central Ravine. It is easy to think of the channel as a static monument, but this is far from the truth. Indeed, the ancient course of the channel in the Greek and Roman periods seems to have been slightly different. Targeted excavations in the Central Ravine in upcoming excavations seasons may yet reveal the exact course of the ancient channel.

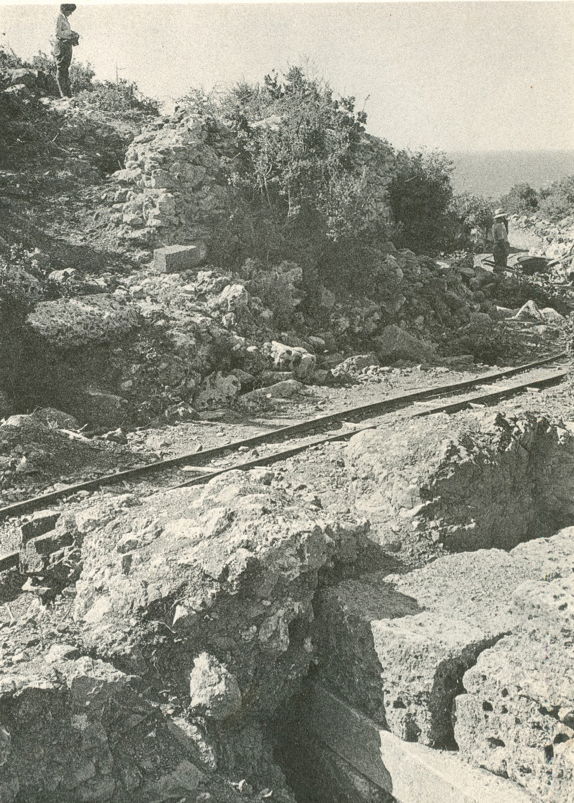

Our modern Central Ravine was formalized by modern excavators as a railroad bed (pictured), extended from the area of the Altar Court and Theater to at least the Rotunda of Arsinoe by 1950. From 1953 to 1956, a series of interventions conducted by the American team resulted in a cement and cobble lined road/river with a culvert below the theater’s cave, or seating section. This modern path was used by tourists during the summer and served as a runoff channel in the offseason. Nature quickly reasserted itself, however, and the channel returned to its ancient use as a water channel by the end of the decade.

The regular storms on the island, which we were lucky enough to witness in the 2017 season, are powerful enough to affect the appearance of the channel on a yearly basis, further underscoring the dynamism of the ancient waterway. The regular need to stabilize the modern ravine walls makes the ravine as much an artifact of modern site management as ancient monument. While the Central Ravine may have physically changed a great deal over time, our attempts to control these natural forces is much the same as those done by the ancient stewards of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods.