Architectural Elements

Propylon of Ptolemy II

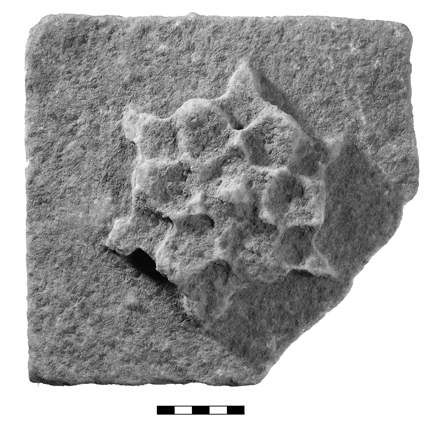

Bukrane and Rosette Frieze, Propylon of Ptolemy II

285-281 B.C.

Dedicated by Ptolemy II

Proconnesian Marble

Samothrace Archaeological Museum; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Istanbul Archaeological Museum

The Propylon of Ptolemy II was one of the most extensively decorated gateways in the Hellenistic Greek world. A skillfully carved frieze of some 104 bukrania and 100 rosettes adorned its entablature. Twelve surviving frieze blocks from the facades and sides indicate the facades has elaborate rosettes with two tiers of petals, while those on the flanks have a single tier of simpler leaves. While most of the building was constructed in Thasian marble, the intricate architectural details, including the frieze, were carved in Proconnesian marble.

Bukrania, or bovine skulls with upturned horns, and rosettes are key elements of sacrificial imagery. The bare skulls represent the sacrificial victim and the rosettes may allude to floral decoration or to phialai, the shallow vessels used for libations (liquid offerings) in religious festivals. These skulls are notable for the varied design of the tufts of hair (forelocks) between the horns and for the beaded ribbons terminating in three-tipped tassels, which hang from the horns.

Sculpted bukrania and rosettes also appear on the Rotunda of Arsinoe II, a building dedicated by the sister and later wife of Ptolemy II. These Samothracian buildings, which have some earliest examples of the bukrania and rosette ornamentation, clearly played an important role in the development of a motif that would became ubiquitous in Hellenistic Greek and Roman architecture.

Corinthian Capital, Propylon of Ptolemy II

285-281 B.C.

Dedicated by Ptolemy II

Proconnesian Marble

Samothrace Museum

The Propylon of Ptolemy II is remarkable in being “bilingual.” While the east façade is Ionic, the western façade that faced into the Sanctuary is Corinthian. The Propylon is one of the first Greek buildings to employ a fully structural, monumental Corinthian façade. Although the Corinthian column was first developed in the late 5th century B.C., this delicate, decorative order was generally reserved for the interior of buildings. Prior to the Propylon, it appears only on the exterior of small structures such as the Lysikrates Monument in Athens.

The Propylon of Ptolemy II is remarkable in being “bilingual.” While the east façade is Ionic, the western façade that faced into the Sanctuary is Corinthian. The Propylon is one of the first Greek buildings to employ a fully structural, monumental Corinthian façade. Although the Corinthian column was first developed in the late 5th century B.C., this delicate, decorative order was generally reserved for the interior of buildings. Prior to the Propylon, it appears only on the exterior of small structures such as the Lysikrates Monument in Athens.

Mixing the Ionic and Corinthian orders was also highly unusual. The designer of this building may have used the two different forms cleverly to distinguish between “outside” and “inside” the sacred space, as the initiates would be greeted by the Ionic façade on entering the Sanctuary and the Corinthian façade once they were inside.

At least 138 fragments of Corinthian capitals were discovered in the course of excavations in the vicinity of the Propylon of Ptolemy II. Individually, they are small, but collectively they allow for a complete reconstruction of the capital. The image to the left shows a plaster reconstruction. Significant features of this capital include the two tiers of acanthus leaves at the base and the exceptionally large diagonal volutes.

Although different in proportions and details, in basic scheme this Corinthian capital closely resembles the engaged Corinthian capital from the interior order of the Rotunda of Arsinoe II. The resemblance in the capitals (as well as the frieze mentioned above) constitutes an additional architectural link between the two buildings that were donated by the Ptolemaic siblings, Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II.

Corinthian Anta Capital with Griffins and Stag, Propylon of Ptolemy II

285-281 B.C.

Dedicated by Ptolemy II

Proconnesian Marble

Samothrace Museum (on loan from the Louvre)

The capital that crowned the anta on the western Corinthian façade of the Propylon of Ptolemy II is known as a “sofa” capital because of the sofa-shaped border that frames the central relief.

Although the subject of its decoration, griffins (mythical, hybrid beasts with the head of an eagle and the body of a lion) bringing down a stag, is a popular Hellenistic motif, figural carving on an anta capital is highly unusual in Hellenistic Greek architecture. In fact, this type of decoration is known elsewhere only on the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, which was completed after the Samothracian Propylon.

Fieldstone Building

First to second quarter of the 4th century B.C.

Fragments of painted plaster from the exterior and interior walls

Eastern Hill

W ca. 6.75 m (across the walls) L at least 9.17 m

Painted plaster exterior fragments: 65.1025, 66.0744.1, 66.0890.1, 66.0771.1, 66.0772

Both the exterior and interior walls of the Fieldstone Building were finished in plaster. The remains from the outer surfaces of the building are scant, but some fragments of plaster, primarily white and bluish-white fragments, were recovered along the southern face of the Fieldstone Building. Graffiti, drawing or writing scratched into a wall or other surface, and dipinti, painted markings, are preserved on several of the exterior fragments. Recognizable forms, once parts of larger inscriptions, include a theta above and a sigma and an alpha below, a theta alone, an epsilon, sigma, and additional, less clear, markings, and one with a sketch that may be a building. A parallel for this practice may be found in the letters etched into the plaster walls of the Stoa. Within the very fragmentary remains, there is some suggestion that the texts may have been lists of initiates.

The remains of the plaster decorating the interior walls of the Fieldstone Building are particularly impressive. They constitute the earliest example in the Sanctuary of painted plaster imitating stone construction. Projecting panels formed the both the dado and string courses. The orthostate and stringcourse were lightly incised and painted with red lines to emulate the drafted margins of masonry blocks. The wall above the string course was painted a deep red.

The Fieldstone Building is one of the very few examples of architectonic mural decoration on a public building or within a Greek sanctuary prior to the Hellenistic period. At the time of its construction, there were no marble buildings within the Sanctuary. (In fact, there were very few permanent structures at all.) The emulation of a costly marble construction reflects an effort to raise the modest architectural profile of the Sanctuary.

Dedication of Philip III and Alexander IV

Inscribed Epistyle

323-317 B.C.

Dedicated by Philip III and Alexander IV

Marble

Sanctuary, Eastern Hill

T079, T102

These two inscribed epistyle blocks are crucial to our understanding of this important Doric pavilion on the Eastern Hill. The first two words of the beautifully rendered inscription, ΒΑΣΙΛΕ|ΙΣΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΣ, are set out in one line across the epistyle which, at its full length, would have stretched an impressive 10.8 meters across the façade of the building. Five additional fragments from the epistyle preserving additional letterforms contribute important pieces of the puzzle. The plural of basileus (ΒΑΣΙΛΕ|ΙΣ), or king, reveals that the dedicators of the building must have been two rulers who held the Macedonian throne jointly. The only two rulers who fit this description are Arrhidaios, the brother of Alexander the Great who took the name Philip III after assuming the throne, and Alexander IV, the posthumous son of Alexander the Great. As restored the inscription reads ΒΑΣΙΛΕ|ΙΣΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΣ|Α[ΛΕΞΑN]Δ[Ρ]|Ο[Σ ΘΕΟΙΣΜΕΓ]|Α[ΛΟΙΣ, which can be translated as “Kings Philip and Alexander to the Great Gods.”

This costly building, which had a Pentelic marble facade and Thasian side and back walls, is one of the very few dedications made by the blood successors of Alexander. Significantly, they chose Samothrace, the place known to have special importance to Philip II, the father of both Philip Arrhidaios and Alexander the Great, as the place to assert their authority as successors. Thereafter, the Sanctuary became central to Hellenistic royalty.

Marble Floor Pieces from Central Panel

323-317 B.C.

Dedicated by Philip III and Alexander IV

Marble

Samothrace, Museum

The Dedication had a floor composed of marble pieces set in a pinkish mortar. The central area bore a rectangular “carpet,” c. 9.62 m by 7.3 m, of small, diamond-shaped marble blocks. The outer border of irregular marble chips formed loosely trapezoidal fields along the sides of the main panel. Remarkably, parts of the marble floor were never covered over and sections of the marble border panels still survive in their original position.

Ionic Porch

Volute fragment with Restored Ionic Capital

Late 3rd or first half of the 2nd century B.C.

Proconnesian Marble

Samothrace, Museum

The Ionic Porch takes its name from the order of the columns that adorned its façade. Oriented westward, the Ionic porch faces away from the Theatral Complex and would have been visible as the initiates continued on their journey down the Sacred Way to the heart of the Sanctuary in the central valley. It is especially visible when coming up the Sacred Way form the central valley.

The architectural remains of the Ionic Porch have fared far worse than those of the adjacent Dedication of Philip III and Alexander IV, owing both to the circumstances of destruction (the blocks fell over the well-traveled Sacred Way) and to post-antique activity in the region. Despite the comparatively thorough destruction of the Porch, several important fragments of the Ionic capitals survive allowing the reconstruction of its formal components. The key remains include two sizable volute fragments, three fragmentary eggs from the echinus (the circular part of the capital that rests on the column), and a corner piece of the abacus (the rectangular crowning element that supports the entablature).

The capital of the Ionic Porch is less elaborate that the other Ionic buildings in the Sanctuary, especially the Propylon of Ptolemy II and the Hall of Choral Dancers. Like the capitals of the Propylon, it is carved in Proconnesian marble, while the rest of the building is made of Thasian marble.

Floral Coffer Lids, Ionic Porch, Eastern Hill

Late 3rd or first half of the 2nd century B.C.

Thasian Marble

Samothrace Archaeological Museum

One of the finest features of the small Ionic Porch appended to the back of the Dedication of Philip III and Alexander IV was its marble ceiling with recessed panels crowned by floral patterns carved in relief. At least 16 fragments of coffer blocks and 6 separately sculpted lids represent this elegant ceiling.

Coffered ceilings were a particularly favored form of architectural sculpture in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods. At least three buildings – the Ionic Porch, the Hall of Choral Dancers, and the Hieron – included marble ceilings that incorporated multiple sizes of coffers with separately carved motifs in the lids. Floral ceiling coffers do not seem to have been common in Greek architecture, although they became a standard feature in the Roman period. Outside of Samothrace, we find just three major parallels in the Tholos in the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidauros, the Temple of Asklepios Soter in Pergamon, and the Temple of Athena at Illion.

The surviving coffer lids from the Ionic Porch preserve both open and closed floral forms, with at least three distinct types that would have been scattered across the ceiling. The flowers are not generic rosettes. While they do not precisely imitate specific botanical, they do recall several Mediterranean species with broad, flat petals and a lower tier of leaves that would have been common in the Greek landscape and familiar to sculptors and viewers alike. The sculptor’s desire for some degree of naturalism no doubt would have been enhanced with painted colors. Generally symbolic of health, fecundity, and vitality, flowers evoked associations with renewal and growth that must have resonated powerfully with the men and women completing their initiation into the Samothracian Mysteries.

Architectural Elements: Sima with Lion’s Head Water Spout, Ionic Porch

Late 3rd or first half of the 2nd century B.C.

Marble

Samothrace, Museum

Lion’s head waterspouts were a common feature of Greek architecture. In addition to their role as handsome sculptural embellishment, they served a very practical function as part of the gutter. Along the edge of the roof, rainwater was directed out of the animals’ mouths at regular intervals to prevent it from cascading over the entire side of the building. The waterspouts alternated with antefixes, upright elements, usually decorated with floral motifs, that formed the ends of the covering tiles that protected the joints between the pan tiles.

Samothracian lion’s head waterspouts from the Hieron and Hall of Choral Dancers are particularly handsome. Only one small head survives from the Ionic Porch, but it exhibits some of the same Samothracian qualities, including the pronounced vertical furrow that descends across the brow from the parted locks of the mane, the deep-set eyes, and the broad ruff of the mane.